-

Push the image away, pull imaging apart. Just as the mass production of photographic film wound down in the late 2000s, film as an aesthetic took off in digital form. Film became filter, chemicals became obsolete thanks to the immortalizing play of pixels, even as solvents and dyes and reagents continue to course through bodies and landscapes out of frame in Rochester, New York. “All that is solid melts into air” (Marx). As if film had withdrawn from the everyday, as if to use it henceforth would only ever be nostalgic or twee or precious and maybe a bit reactionary. Use it or not, we remain inside the dreamscape and Urform of photochemical capital after Kodak: the snapshot. This form saturates the historical present such that we, too, rehearse its reproduction–instinctively, automatically, instamatically. One becomes two becomes five becomes twenty-eight layers of emulsion coated on the film base. Delaminated and stretched out so that we can get between them, if never quite beneath them. The surface multiplies when you peel it off.

-

To make a snapshot is to call up the history of seeing, to call into being the camera as an apparatus and total situation: mirror, shutter, lens, emulsion, light, shadow, figure, ground, subject, photographer, dust, fog, glare, glance, gaze, every photo ever made. It is an open question how the elements relate, live factors that can only be accounted for in the moment. “The photographer's command, ‘Watch the birdie!’ is essentially a stage direction” (Cavell). Reception is not only baked into the technology but called into being by it. The snapshot is already performance and installation.

-

What makes flypaper flypaper: the paper or the fly? And newspaper? And photopaper? “You press the button, we do the rest” (Kodak). Behold a sculpture and it styles you as an observer. Behold an installation and it styles you as a participant. Installation works through you and works you through. It is a theater whose fourth wall is always more or less open, more or less inviting, more or less sticky. You are inside the camera. The camera is inside you. Light hits the gallery windows. It turns out they were a mirror, the reflection from the street outside was a backdrop, the streetlights in the streetscape were the lighting overhead, and you were the photographic subject (photographed or photographing, who's to say?). A snapshot comes together before your eyes as if it were already there, as if you just realized you’ve been living in an emulsified world. To open up the black box of the camera after Kodak is to discover you were inside of it all along.

-

No instant is an image, no image is an instant. When the two are laminated onto one another, sequential time opens up. You might find you have already fallen in. For the snapshot to exist, we have to be already caught in the camera’s embrace: capture or rapture? Inversion is a signature move of the filmic. There is the opening, there is the mirror, there is cctv. “Paranoids are not paranoids because they’re paranoid but because they keep putting themselves, fucking idiots, into paranoid situations” (Pynchon). You hide, they seek. Reflection turns the windows into all surfaces, and the street lights become stage lights for a selfie. Pynchon’s missing proverb: there can be play inside here, beyond even the pleasures of the secret.

To pose for or use a camera and participate in imaging calls up performances of the photographic space and photographic relation. The photographic relation is not self-transparent. “The audience takes the position of the camera; its approach is that of testing” (Benjamin). The good life imagineered after Kodak takes the white nuclear family as its vanishing point, reproduced when the affordances of photochemistry and technical instruction combine to channel desire this way and not that, to posit and style modes of self-fashioning and intimacy with others one shot at a time. To make a snapshot is to call into being a future subject who will take pleasure in the memory that is being made. It’s a wish for continuity.

-

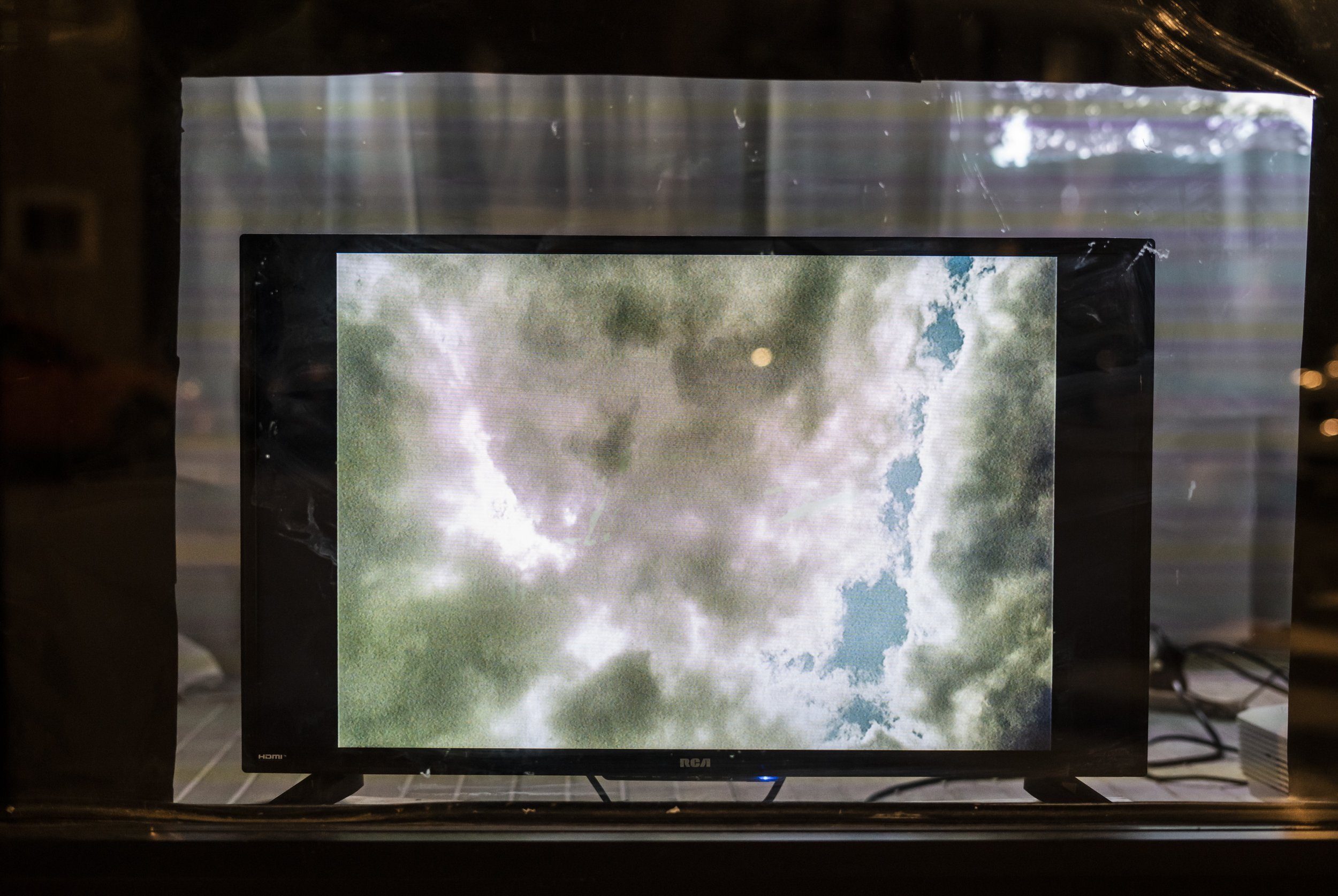

In 1895, Bertha Pappenheim (aka Freud’s patient Anna O) took daydreaming up a notch. She developed the art of self-hypnosis. The name she gave to her lapses into unconsciousness: clouds. In 1904, panchromatic film split blue from red and lit up the sky to image a new photographic reality: clouds. Cinema’s inside joke: all the world’s still a stage. Kodak’s inversion: all the world’s a stage still. Who gets the last laugh? To wear away a fantasy when attachment oversteps: stock up on lightbulbs. Leave the slide in the projector for 21 days. There is no up or down here; don't worry if it won't advance. Like sky-clouds, image-clouds fade: put a slide in a window, watch the light come in, see the image appear, fade, and degrade the emulsion. The image-cloud decays and returns to thin air. Stay in the clouds until they lose their referent and heat wears away the emulsion.

-

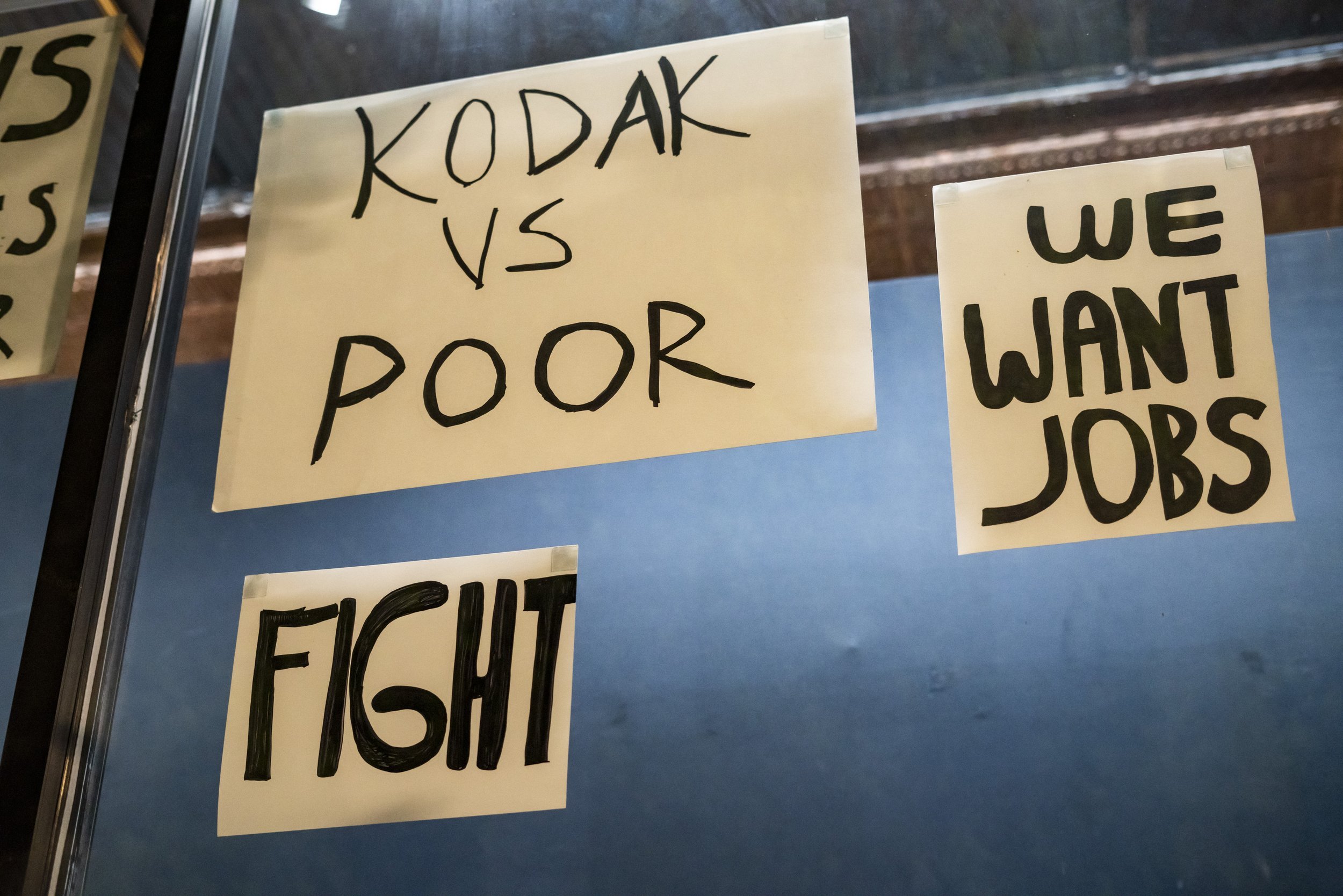

All of the materiality, the blood, sinews, muscles and so on, all of the workers who put the clouds in the sky at Kodak, who could have stopped the machine from moving forward were, also, caught up in the clouds. Where would a cloud dweller dwell if the clouds burnt off? “The thing about revolution is that it changes things” (Romer).

-

How could a single corporation craft a singular visual habitat that becomes the archival structure that will format how our memories and attachments endure and degrade? “Once again we stand in awe of gigantic entities massively distributed in time and space, in such a way that we can only point to tiny slices of them at a time. Once again we find our faith shaken.” (Morton) The corporation waxes immortal in its monumentality. The grandeur, grandiosity, of the corporate form whose magic tricks push us into a world stylized after its imaging powers. Magical thinking: a human habit of drawing nourishment from thin air by desiring that reality conform to fantasy. Born unstable, it holds the possibility for play, laughter, tragicomedy, diversion. The magical thinking of the corporation: grotesque ideas from wooden brains, the world upside down, the despotism of the means of production, fantasy distorted into machinery. The corporation manufactured the dream, crystallized a world in which the creep creep creep of extraction into imagination standardizes capacities for dreaming. The inverse of magical thinking: burning off the clouds.

-

Burn off the clouds the way clouds burn themselves off, degrading in the blazing light of the sun. It is possible to remontage an image, tease open the process of getting attached and letting go, and refuse the snapshot’s loud because unspoken messaging about “the way we were.” The historical, shareable scales of injury: what cannot be repaired can sometimes be remediated. “All understanding begins with our not accepting the world as it appears” (Sontag). Film, for all of its wreckage, remains an incredibly flexible medium; you can push it, pull it, and it can be induced to materialize that which it's not supposed to materialize. The chemical decay of and in film is a form of historical commentary all of its own: it is an opening resistance of material to the forms imposed on it. Decay is in some ways a refusal of the infinite extension of one future audience over another, the audience fashioned after Kodak, the white nuclear post-war American family. If decay is not inevitable, if decay is intentional, then can it be occupied strategically, the no longer cared for? The inverse of abandonment is letting go.

-

Take another one just in case; use up the last shots on the roll; get a disposable camera for the kids to take with them; take another one just in case; put the best pictures in the album; get a second set of prints for free; it’s digital, no need to save film, take a dozen just in case; tag your friend in the shot, tag your friends who weren’t there. The content is real. The form is everything. The Kodak moment never stands still.

-

It is difficult to get rid of something that is no longer there. That ultimate paranoid, the sovereign, will happily lose their head in the immortalizing form of currency. Minted and put into circulation, jangling in pocket and rubbed between fingers, the image-sovereign goes on and on about how the machinery of commercial society, no matter how virtual its tokens and would-be departures from mercantilism aka big government, cannot do without the stamp of political authority, whose reach capital promises to extend and yet proportionately devalues. Lender of last resort; bank bailout; tax cuts; industrial subsidy. The corporate form eats at the table of state, and then slowly begins gnawing at its legs.

-

“Nothing to see here” puts everything on display.

You can view documentation and read more about the exhibition here.